Caring for the Earth: Reasons for Hope

Caring for the Earth: Reasons for Hope

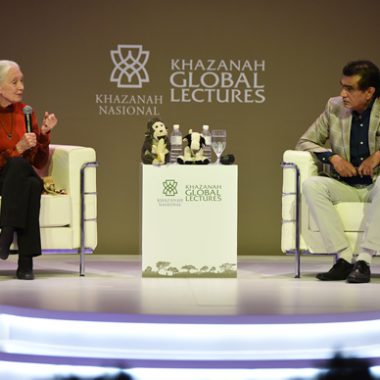

Dr Jane Goodall DBE

Founder - The Jane Goodall Institute & United Nations Messenger of Peace

Dr Jane Goodall DBE is a world-renowned ethologist, conservationist and United Nations Messenger of Peace. Considered to be the world’s foremost expert on chimpanzees, she is best known for her 56-year study of social and family interactions of wild chimpanzees in Gombe Stream National Park, Tanzania. She is the founder of the Jane Goodall Institute and the Roots & Shoots programme, and she has worked extensively on conservation and animal welfare issues.

In July 1960, at the age of 26, Jane Goodall travelled from England to what is now Tanzania and bravely entered the little-known world of wild chimpanzees. She was equipped with nothing more than a notebook and a pair of binoculars. But with her unyielding patience and characteristic optimism, she won the trust of these initially shy creatures, and she managed to open a window into their sometimes strange and often familiar-seeming lives. The public was fascinated and remains so to this day.

The Jane Goodall Institute (JGI)

In 1977, Dr. Goodall established the Jane Goodall Institute (JGI), a global non-profit focused on inspiring individual action to improve the understanding, welfare and conservation of great apes and to safeguard the planet. With 3 offices around the world, the JGI is widely recognised for innovative, community-centred conservation and development programmes in Africa. Its mission is based in Dr. Jane Goodall’s belief that the well-being of the world relies on people taking an active interest in all living things.

JGI supports community-centred conservation throughout Africa’s Congo Basin, engaging with individual stakeholders to garner long-term conservation impact; additionally, support young people in more than 130 countries across the globe as they work to make positive change in their own communities. JGI’s cutting-edge use of technology ties its high-impact

conservation work in Africa to its citizen-science projects led by youth groups across the globe.

JGI’s multifaceted efforts – to protect great apes and their habitats, to improve human livelihoods, and to encourage the next generation to care for the world

– creates an integrative approach to achieve Dr. Goodall’s vision of earth as a place where people, animals, and the environment exist in sustainable harmony.

Roots & Shoots

Roots & Shoots is a programme of the Jane Goodall Institute. The programme is about making positive change happen for people, for animals and for the environment. The Roots & Shoots network connects youths of all ages who share a desire to create a better world, with young people identifying problems in their communities and taking action.

Awards and recognition

Dr. Goodall has received many honours for her environmental and humanitarian work, as well as others. She was named a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire in a ceremony held in Buckingham Palace in 2004. In April 2002, former Secretary-General Kofi Annan named her as a United Nations Messenger of Peace.

Her other honours include the Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement, the French Legion of Honour, Medal of Tanzania, Japan’s prestigious Kyoto Prize, the Benjamin Franklin Medal in Life Science, the Gandhi-King Award for Nonviolence and the Spanish Prince of Asturias Awards. She has received many tributes, honours, and awards from local governments, schools, institutions, and charities around the world.

Well, thank you for a wonderful introduction and thank everybody who is here tonight. I’m going to greet you in my traditional way, and I’m willing to bet that the voice of the wild chimpanzee has never been heard in this room before. And if you’re with me in the hills of Gombe, and you climbed up in the morning, you would almost certainly hear the chimpanzees greeting the day.

(Jane Goodall imitates a chimpanzee call) This is me, this is Jane.

Well, you’ve just heard all this stuff about my life, and what I’ve done in my 82 years. And sometimes, I really wonder how it’s all happened. How is it that when I go to a country like Malaysia, all of you people have come to listen to me? And I’ve worked out that there are actually two Janes. There’s one Jane that has become somehow the sort of conservation icon, and I think it probably started with the National Geographic Society. But there’s also the other Jane, and that’s me. I’m just me, just an ordinary human being who started off as a very shy little girl with a dream.

I want to thank one person in particular and but for her, I think possibly I would not be standing here tonight. We can’t choose our parents, and I was lucky. I was born with an extraordinary mother, I was also born loving animals. When I was one and a half – I don’t remember this, of course – but she tells me she came into my room to say goodnight to me, and she found I had taken a whole handful of earthworms to bed with me. Well, most mothers would be kind of cross because there was a lot of earth in the bed as well but she just said quietly ‘Jane, they need to go back into the garden or they’ll die.’ And we carried them back.

And then, when I was four and a half, and I don’t know how many of you can think of a four and a half year old – I’m sure quite a lot of you – and loving animals but living in London, there weren’t so many animals. And so, what I remember so well was going for a holiday into the country and staying on a farm. And in those days, farms were farms where animals roamed about in the fields, there was none of this intensive farming. And meeting cows and pigs and horses face to face, was really exciting. And they gave me a job to help collect the hen’s eggs. And the hens were pecking around in the farmyard but they mostly went into these little henhouses where they also slept at night, to lay their eggs. And the eggs were in little boxes around the edge, and I would go and lift up the lid and if there was an egg, put it in my basket. But apparently, I began asking everybody, ‘but where’s the hole on the hen? Where does the egg come out? I couldn’t see a hole big enough for an egg.’

And obviously, nobody told me to my satisfaction. And what I do remember so clearly is seeing a hen, she was a brown hen, and she was going into one of these hen houses, I think there were about six or eight of them, and thinking she’s going to lay an egg, and crawling after her. Well, that was a big mistake. And with squawks of I suppose fear, she flew out. And you know, I – four and a half years old – but I thought well, no hen would lay an egg here. This is a frightening place. And I went into an empty hen house and hid in the straw at the back and I waited and I waited and I waited. And the family had no idea where I was. And as it was beginning to get dark, they were searching and in fact, they even called the police. And yet, when my mother met me, instead of ‘how dare you go off without telling us? Don’t you dare do it again’ which would have killed all the excitement, she saw my shining eyes and sat down to hear the wonderful story of how a hen lays an egg.

And I can still close my eyes and see it as though if it was happening yesterday. And the reason I tell that story is isn’t that the making of a little scientist, the curiosity, asking questions, not getting the right answer, deciding to find out for myself, making a mistake, not giving up, and learning patience. It was all there, in that little four and a half year old girl. And with a different kind of mother, that little scientific curiosity might have been crushed.

And that’s why I say I might not be standing here tonight. She decided that if she got books about animals, I would learn to read more quickly, and of course, she was right. The war in 3 Europe had started by this time, and I don’t think they were even making new books, so my books came from the library. Anyway, we had very little money. And so one day, I was given from the library this book about Dr Dolittle, someone who could actually talk to the animals, and he was taught by his parrot Polynesia. And if you don’t know the Dr Dolittle stories, they are wonderful. And I wanted a parrot to teach me animal language, and so I was eight years old, and I pretended to all my friends that I could understand the dogs and the cats and the squirrels and the birds. They believed me, I would translate what they were saying.

And then when I was 10, as I say, we had very little money and the books mostly came from libraries. But there were some wonderful secondhand bookshops, and this one particular one was run by a funny little old man. And really, the books were just piled up higgledy piggledy, he didn’t know where anything was. And I used to spend hours in there and I found this little book, I just had saved up enough of my few pennies pocket money to buy it. And I took it home and I climbed my favourite tree in the garden. I read that book from cover to cover. I still have it today, and that was called Tarzan of the Apes.

And of course, I fell passionately in love with Tarzan. Little girls of 10 are very romantic. And what did Tarzan do? He married the wrong Jane. Well, of course, I was very jealous. But equally, I knew that there wasn’t a Tarzan. That’s when my dream began. I will grow up, go to Africa, live with animals and write books about them. That was my dream. And everybody at school laughed at me: ‘how will you get to Africa, it’s very far away.’ We talked about it as the Dark Continent, we didn’t have any money. And girls didn’t do that sort of thing. ‘Jane, dream about something you can achieve, forget this nonsense about Africa.’ But not my mother. And what she said to me, or at least words to this effect, is the message that I take around the world today and share with children everywhere.

Basically, she said ‘Jane, if you really want this thing, you’re going to have to work really hard. You’re going to have to take advantage of opportunity and never give up.’ And I think one of the most rewarding things about my life today is the number of children whom I meet or who write to me and say, ‘you taught me that because you did it, I can do it too.’ I can’t think of anything more rewarding than that.

So as you heard, there was no money for university. You couldn’t get a scholarship unless you were good in a foreign language. And we had just enough money for this secretarial course. And when I got the letter from my school friend … you couldn’t save money in London where I was working at that time, so I worked, I think it was about five months in a hotel, an old fashioned hotel where people came for a week’s holiday, and after the war, they didn’t have much money. So, I was serving breakfast, lunch and dinner. And always, when I’m at an event like this, I’m always thinking of the waiters and waitresses, and what a hard job they actually have. But at any rate, thank you waiters and waitresses if you are listening in here.

So as you heard, there was no money for university. You couldn’t get a scholarship unless you were good in a foreign language. And we had just enough money for this secretarial course. And when I got the letter from my school friend … you couldn’t save money in London where I was working at that time, so I worked, I think it was about five months in a hotel, an old fashioned hotel where people came for a week’s holiday, and after the war, they didn’t have much money. So, I was serving breakfast, lunch and dinner. And always, when I’m at an event like this, I’m always thinking of the waiters and waitresses, and what a hard job they actually have. But at any rate, thank you waiters and waitresses if you are listening in here.

So eventually, I had saved up enough money, by boat which is how one went in those days. It should have been a journey taking about slightly less than two weeks, from Britain through the Suez Canal and down to Mombasa. But there was this stupid little war between England and Egypt, and the Suez Canal was closed. And so, the boat went all the way around Cape Town, took over three weeks. And can you imagine what it was like? I was 23 years old, and I got onto the boat and it was grey and dull in England, and the water was grey. And then, as we went further south, so the water got bluer and the air got warmer. And I can never forget the first flying fish, and the dolphins that were gamboling around the boat as we got down to Cape Town.

Arriving in Mombasa, going by train, all the animals were there then, we went past them in the train, being met by my friend. And the very first morning I woke up, she came running to my room and said ‘Jane, come and look.’ And there, just outside the house were the paw prints of a large male leopard. Now, I had really arrived in Africa.

And how wonderful to hear about Dr Lewis Leakey, and somebody said ‘Jane, if you’re interested in animals, you should meet Lewis.’ And he was curator of the National History Museum at that time. And I made an appointment to see him, just to talk about animals. And he took me all around, he asked me many, many questions about the different animals that were in the museum. And because I had read so many books about Africa and animals, because I had spent hours when I was in London in the Natural History Museum, I could answer most of his questions. And so, that’s why he gave me a job as his secretary, assistant, took me on one of his digs to Olduvai Gorge in the days when all the animals were there. Meeting rhinoceros long before they became endangered, meeting a young male lion who followed me and this other young girl, at least the length of this large room, which was a bit scary but very exciting.

And I think it was that evening, around the campfire, that Lewis decided I was the person he’d been looking for. He said for years to go and learn about chimpanzees in the wild, nobody knew anything, nobody had studied them in the wild. And he was searching for the fossilised remains of our earliest ancestors. And you can tell an awful lot from the fossils about those creatures from the wear on the teeth, the sort of diet they had, and from the structure of the bones, the sort of gait, the way they walked. And from the remnants of tools on the living floors, you could tell the level of their sophistication. But behaviour doesn’t fossilise.

And Lewis argued that if we could, if I could find behaviour that was similar or even the same in chimpanzees, our closest living relatives today, similar behaviour in them and us, maybe that behaviour was present in the common ancestor about seven million years ago. And therefore, he could better imagine early humans, kissing, embracing, holding hands, patting one another on the back, perhaps waging war. All of those things which I was to find out, similar in chimpanzee and human society. But none of that was known when I first got to Gombe National Park.

It took him a year to find money. I mean, who was going to give money for this, young girl with no degree, new out of Africa. So I had go back and wait in England while he searched and searched for money. And eventually it was a wealthy American businessman who provided money just for half a year. He said, ‘well, we’ll see how she does.’

And then at that time, you know, the British Empire was crumbling but it was still in its last throes. And what is Tanzania today was Tanganyika, and it was under British protectorate rule and the authorities were not prepared to take responsibility for this young girl. It was ridiculous. But in the end, because Lewis never gave up, they said, ‘oh well, all right, but she can’t come alone. She has to come with a companion.’ And who volunteered? That same amazing mother. She packed up for four whole months, and left her life in England, and shared an old ex-Army tent, none of your neat little zips that you have today so that you can shut out the mosquitoes, no. If you wanted air, you rolled up the side flaps and in came the air, yes, but also snakes and spiders and goodness knows what.

And it was fine for me, I was up in the hills every single morning, searching for chimpanzees. But she was left on her own in the camp and there were buffaloes around at that time. But she set up a little clinic for the local fishermen. And although she wasn’t a doctor or a nurse, her brother was a surgeon, her sister was a physiotherapist, and we’d come armed with simple things like aspirin and bandages and so forth. And because she spent hours with the different people who came with their ailments, she made some amazing cures, and people began coming from further and further away. And I learnt later that she was known as a white witch doctor. The good kind.

So, she established, for me, from the very beginning, a really good relationship with the local people, and these were fishermen coming down over the hills to the shore of Lake Tanganyika. And then when the moon was full and the fish didn’t rise to their lights, they went back to their village and sold the fish. So she did another really important thing for me because in those early days, the chimpanzees would take one look and run away. They are very conservative, they have never seen a white ape before. And they would take one look and vanish in the vegetation.

And I was in my dream world but you know, I knew if I didn’t see something exciting before the money ran out, that would have been the end and I would have let Lewis Leakey down. So, it was wonderful when I got back in the evening, there she was, and she was boosting my morale. ‘Jane, you are learning more than you think. You found this peak that you said, and from it, you can see the chimpanzees moving around, sometimes alone, sometimes in small groups, sometimes obviously a family – a mother and her younger children.’

She said, ‘you’d seen them all meet up and greet one another when there’s a delicious fruit come into season. And you’re learning a lot more than you think. You see how they make nests at night, bending over the branches,’ just like your orang utans do here. So, she did help to boost my morale. And it was really sad that she left before the breakthrough observation which was when I saw a chimpanzee through the vegetation, with my binoculars, I saw a black hand reach out and break off a grass stem and push it carefully into a termite mound, leave it for a moment, pull it slowly out and pick off the termites with his lips. And I saw him break off a leafy twig, and before he could use that as a tool, he had to strip the leaves. He was making a tool.

That wouldn’t be exciting today, we know today that various animals can use and make tools. Birds, crows have been known to make tools. But in those days, it was really exciting because it was thought in our arrogant way, that we humans were the only individuals, only creatures to use and make tools. We were actually defined as man the tool maker. So that when I sent Lewis Leakey this information, waited of course until I had seen it a few more times with a few more chimps to be sure, he said well, we shall have to redefine man, redefine tool or accept chimpanzee as human.

So, it was that that brought in the National Geographic Society. And not only did they provide money so that I could relax, knowing that the study could go on after the six months was over, but they also sent a photographer and a cameraman Hugo van Lawick who became my first husband and the father of my only child, my son.

And so, as the chimpanzees came to accept me, thanks really to this one individual David Greybeard who I had seen using and making tools, who’s the first one to demonstrate that sometimes chimpanzees hunt and eat meat, not very often but sometimes. And because he began to accept me and not run away, if he was with a group that were all ready to flee as usual, and David just sat there calmly, the others would look from him to me and back, and I suppose they thought well, she can’t be so dangerous after all.

And so, in a way, he introduced me to his friends in the forest, and there was his close companion Goliath. And then there was the very low-ranking Mike, and there was the old female Flo, and Melissa and Passion and all the rest of the characters that I got to know so well. And as the months turn into years, I began to realise that there are good and bad mothers in chimp society just as in human society. And the good mothers are those who are protective but not over protective. They allow their child some freedom, they are affectionate, they are playful but most importantly, they are supportive. In other words, my mother behaved like a good chimpanzee mother.

And it was very clear as I learnt more and more that the offspring of the good mothers did better, they became more self-assured. The males rose higher in the dominance hierarchy, the females were better mothers. And learning more and more about the ways they resemble us in their communication, gestures, kissing and embracing, and holding hands and patting on the back, and swaggering and shaking the fist.

And yes, I learnt that they, like us, have a dark side. They can be violent and brutal but like us, they can show compassion, altruism, true altruism as when a mother dies, leaves a small infant. If that child is older than three years and no longer dependent on the mother’s milk, then the child will have a chance of surviving, if it’s cared for and that’s usually by an older brother or sister. But if there’s no older brother or sister, then an unrelated individual may care for that infant, and the infant may actually survive.

So it was when I had been in field two years, didn’t know all of this by then but I was beginning to learn quite a bit about the chimpanzees and I certainly knew their various personalities. And I got a letter from Lewis Leakey telling me that he wouldn’t always be around to help me get money, I would have to stand on my own two feet and I would need a degree. And there was no time to mess about, as he put it, with a BA. I would have to go straight for a PhD, and he had me a place, Cambridge University.

Well, you can imagine I was a little bit nervous. I had never been to college. I imagined that the other students resented me, ‘who does she think she is? You know, coming in just because she studied exotic things like chimpanzees, she thinks she doesn’t have to do all the work for a BA.’ It wasn’t like that at all but they didn’t know. But then when the professors told me that I had done everything wrong, that was a blow. I shouldn’t have given them names, they should have had numbers, that was scientific. And I shouldn’t be talking about them having personalities, minds capable of thinking and absolutely not emotions. I was guilty of the worst scientific sin of anthropomorphism. Well, fortunately, when I was a child, I had a wonderful teacher. And that teacher had taught me that of course, animals have personality, of course they can think, and of course they have emotions like happiness and sadness and fear and despair. And that teacher? That was my dog, Rusty.

Yes, let’s give dogs a hand.

If you share your life in a meaningful way with a dog, a cat, a horse, a cow, a bird, I don’t care what it is, you know the professors were wrong. And fortunately my sternest critic, initially, was my supervisor Dr Robert Hinde, but then he came to Gombe and he said in two weeks there, he learned more about animal behaviour than in all his previous life. And he helped me to write my observations in such a way that I wouldn’t be completely torn apart by my scientific colleagues. And I got the PhD, and I went back to Gombe and I built up a research station so that other students could come and help to learn more and more about the chimpanzees. It was my dream life. I had a child by then, he was there with me, he was being home schooled. And I had time for analysing the data which I had loved doing, time for writing some popular books, and I had time every day to be out in the forest with the chimpanzees who were just out in nature.

So why did I leave? I left because in 1986, we brought together the various people who by then was studying chimpanzees in eight different parts of Africa. And it seemed important to try to share the knowledge that we jointly had. Because we now know that chimpanzees have simple cultures, the young ones learned by observing and imitating, and one definition of human culture is behaviour passed from one generation to the next through observational learning. And so bringing these different people together, looking at slides at how the chimps behaved differently in different parts of Africa, it was really exciting but we had a session on conservation.

And that was a shock, everywhere, all of these eight different places, chimpanzee numbers were dropping, forests were disappearing. There was the beginning of the bush meat trade, the commercial hunting of wild animals for food, chimpanzees were being caught in wire snares and losing a hand or a foot or dying. The mothers were being shot to steal their babies as pets, to sell in the local markets or to sell overseas through dealers to be exhibited in zoos in far off lands, to be used in the entertainment business in circuses and so forth. And at that time, in medical research.

We had another session on conditions in some captive situations, and that was an even worse shock, seeing the cruelty with which the chimpanzees are trained to perform in a circus. And this was undercover, of course, nobody was going to admit the cruelty but there were people who found, there were whistle-blowers.

And then, came worst of all, secretly filmed footage in a medical research lab. Our closest living relatives, they were there because their bodies are so like ours, we share over 98 per cent of DNA, composition of DNA with chimpanzees. The immune system, the composition of the blood, the anatomy of the brain, all of these things are so like us. And so, the scientists were very happy to use these bodies because chimpanzees can be infected with diseases which other animals, less like us, cannot be infected with. Yes, so here we are, we have the perfect model. We learn about ways to cure disease, vaccines and so forth with these chimpanzees. And they were not prepared to admit the equally striking psychological similarities between us and them. And so here were these close relatives of ours, in five foot by five foot, bleak cages with bars all around. I actually have stood in one of those cages with maybe if they were lucky, with limited time on the ground. Maybe for 30 or 40 years, they can live for 60 years. I couldn’t sleep for weeks after that, these images went round and round in my mind.

So, I went to that conference in 1986, 30 years ago, I went as a scientist with a magical life and I left as an activist. I didn’t make any conscious decision, I just left knowing that I had to try and do something for these amazing beings who had taught me so much. They taught all of us so much. It was chimpanzees because they are so like us in so many ways that finally began opening the mind of science to understand that we are a part of, and not separated, from the rest of the animal kingdom. And honestly, in 1961 when I went to Cambridge, it was thought that the difference between us and all the other animals, was one of kind. Now we know that it’s one of degree but back then, it was one of kind. And it was a sharp line which should never be crossed.

And as I say, because chimps are so like us in so many ways, gradually, science opened its mind, and you know that today, for you young students, any of you who want to go into animal behaviour, this is the most exciting time because we are now understanding that all kinds of animals that we never thought were particularly intelligent before, or at least science didn’t, now we find that they are capable of amazing intelligent behaviour.

The crow, I mentioned before. And the octopus. It’s unbelievable what octopus can do, and if you haven’t seen this, then I beg you afterwards google octopus and coconut shell. And you will be amazed to see what happens as an octopus under the water, a wild octopus, with two tentacles on each side, walking on the other four, goes across the ocean bed with half coconut shells on each side of him. And when he gets to an area where there are no rocks, and he’s of course soft-bodied, he lays one half on the coconut shell on the ground, he gets himself wriggling, wriggling, making himself smaller and smaller and smaller, until he’s more or less inside the bottom half, and then he reaches out and puts the top half over him. This is magic, and it hasn’t only happened once, does it with clam shells as well, different octopus.

So here we are, it’s wide open. The animal kingdom has never been so wide open to exploration. And this is just one reason why, in Malaysia, you’re so lucky with the amazing animals that are out there, and I saw a film and some photographs this morning of some of these extraordinary animals that you have here in Malaysia.

But at any rate, as I say, I left that conference as an activist and since then, 30 years, I haven’t been more than three weeks in any one place consecutively. And I began travelling around in Africa, I thought I must learn more about what’s happening to the chimpanzees and their forests. And so, I learnt a lot but at the same time, I was learning more and more about the problems faced by so many African people, those living in and around the rainforest, suffering from tremendous poverty and hunger, and a lack of educational and health facilities, struggling to survive. And this all came to a head in 1991, when I flew over Gombe National Park which had been part of a belt of forest stretching along the western part Tanzania and Uganda, and curling around to the west coast of Africa. But I flew over in ’91, I looked down on a tiny island of forest, surrounded by completely bare hills. More people living there than the land could support, overused farm land, no longer fertile. People desperate to try and grow more food to feed their families, and so cutting down the last of the trees. Steep, steep country so as the tree cover disappears, there was terrible erosion and the soil washed down into the little streams which were getting silted up. And I realised, it hit me so forcibly, we can’t even try to save these chimpanzees while people are living in this terrible situation.

And so, that’s when the Jane Goodall Institute began our programme that we call Take Care, or TACARE, and it’s – I won’t get into it now – but it’s basically a very holistic programme because everything is inter-connected. And it was growing more food, and obviously without chemicals. But they also wanted better education and health facilities, and we did this by working with the Tanzanian government. We had very little money, a small grant from the European Union.

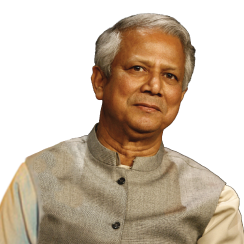

And then introducing projects to restore the flow of the streams, protecting the watershed, beginning to allow the steep hills to reforest from the seeds in the soil, and introducing the micro credit programmes, and I was so happy to see Muhammad Yunus made one of these lectures, he’s one of my true heroes. He took me with him to Bangladesh, he introduced me to the women whose lives have been changed when they took out a tiny grant. And what I’ve noticed as we have developed this, we have nine of these little micro credit lending areas just around Gombe, is that if you just don’t hand out money but you loan the money, and you loan it for some environmentally sustainable project, like one woman wanted to start a pineapple farm, another one wanted a few chickens to sell the eggs, and then they pay back. When they pay back, they can, if they wish, take out a larger loan but because they have done it themselves, they have been able to pay back, they are proud, I did it. And so, they are empowered and carrying on with this same theme, we provide as many scholarships as we can to keep girls in school after puberty. And it’s been shown all around the world that as women’s education improves, as women are empowered, so family size tends to drop. And that is desperately important in the world today. And we provide family planning information which is delivered by women in the villages, not by us. In fact, all of this programme has been done by local people, we’ve kept right in the background.

So successful has this Take Care / TACARE programme been that we’ve been able to introduce it around chimpanzee habitat in seven other African countries, and it has been successful in all of them. So helping to save the environment and the chimpanzees by helping the people. And the people are now truly our partners in conservation. We work around Gombe in 55 villages now and all of these villages provide one or two, depending on the size of the village, one or two volunteers to monitor the forests that are now coming back. The trees are growing where we once saw the bare slopes, some of them are 30 foot high already. And they go out, and now, they’ve got smart phones and i-tablets and things like this, and they use GPS, and they can go and monitor where there is an illegally cut tree, or where there is an animal trap or a cartridge. But they can also monitor a chimpanzee nest or a sighting of a leopard and so on. And all of this information goes out to a platform in the cloud, Global Forest Watch. And it’s adding to what people are trying to do around the world to protect our precious rainforests. So, as I was traveling around developing this programme, and also trying to raise funds for these programmes, I was learning more and more about what was happening to our planet.

Let me go back for a moment to the chimpanzees. I talked a lot about the similarities between them and us, but clearly, there are major differences as well. You won’t have chimpanzees dressed up in jackets and ties, and pretty dresses for a dinner, listening to a lecture. And chimpanzees are way smarter than we used to think, they can learn more than 400 of the signs of the American Sign Language (ASL) and use them in meaningful ways. Some of them love to paint, some of them will spontaneously sign to you what they think they have painted. It may not look like it to you but one painting I have is labelled Banana Flower. That’s what the chimpanzee said it was. They can also do very, very clever things on computers, remembering the order of numbers much faster than I can.

But chimpanzees can’t make rockets going up to the moon or to Mars, and I think personally, the biggest difference between us and them, us and any other animal, is this explosive development of the human intellect. And I believe a main contributory factor of this development is that we, at some point, developed this way of communicating with words so that we can learn from the distant past. We can make teach children about things that aren’t present, we can make plans for the distant future. I mean, I could plan to come back here in three years.

And most important of all, we can have discussions. We had a discussion this morning, a roundtable and when we bring different people together, as this morning, there were corporates, there were NGOs, there were scientists, conservationists, and discuss problems, then this sometimes leads to solutions. So, isn’t it peculiar that this most intellectual creature that has ever walked on planet Earth, surely we are, nevertheless we are destroying our only home. That’s not very intelligent, is it?

So, what’s happened? It seems to me that there’s been some kind of disconnect between this really clever brain and the human heart, love and compassion. And I have this conviction that we can only attain our true human potential, we can only begin to heal the harm we have inflicted on this beautiful planet when head and heart work in harmony. And when we realise that there is more to life than the bottomline.

And I think that one of the things that has gone wrong is that while we all need money to live, there are too many people today who live for money. And I always like to say it’s fine to live for money, if you live for money to make the world a better place like donating money to the Jane Goodall Institute, for example. At any rate, as I’m going around learning more about the pollution, the destruction of the rainforest, the creation of greenhouse gases, the CO2 that is released when you cut down and burn a forest, the gradual pollution of the ocean, the heating up of the ocean as the ice is melting thanks to global warming, these greenhouse gases that form an envelope around the planet and trap the heat of the sun. Then, I’ve been in Greenland, I’ve seen the ice melting at a time of year when no melting should take place. I’ve met people who’ve had to leave island homes because the melting of the ice has raised the level of the ocean, and there’s been an increase in storms and hurricanes and so forth. And so, at high tide or during storms, their homes had been flooded and they had to leave their islands. And it’s only getting worse.

Not really surprising that as I’m traveling around the world, I’m meeting a lot of young people, high school students and university students particularly, but also young people out in their first jobs. Well, and everybody really, meeting people of all kinds in all these different countries, who seem not to have much hope for the future. And it’s not really surprising when you think about what’s going on. I began talking to these young people, particularly, because if our young people lose hope, well then there is no hope, right, because there is no hope at all. So, I began talking to them, and basically, they all said more or less the same thing. ‘Well, we feel like this because you’ve compromised our future and there’s nothing we can do about it.’

Have we compromised the future of our young people? Have we compromised the future of our children and grandchildren? We have. We know we have. I know the planet’s changed since I was a young child, and it’s not changed for the better. And I’m so tired of hearing this phrase ‘we haven’t inherited this planet from our parents, we borrowed it from our children’. We haven’t borrowed anything, we’ve stolen, and we are still stealing. And it’s time we get together with the young people and to try to heal the harm that we have inflicted before it’s too late. Because I don’t believe it when people say it’s too late. I think we have a window of time to turn things around.

So, that’s when I began the programme for young people, Roots and Shoots. It began in Tanzania with 12 high school students. They came and told me all the things that were bothering them like the destruction of the coral reef, the street children. They were worried, some of them, about the treatment of animals in the markets, and stray dogs. They were worried about all kinds of things like that. And they wanted me to fix all those problems. And I said I love Tanzania but I’m not Tanzanian. And I really can’t fix these problems but maybe together, we can talk about them. So, they got friends from their schools, they came from nine different schools, and we had a big meeting, and from that meeting, this youth programme was born. The main message: every single one of us, every single one of us makes impact on this planet every single day. We cannot live through a day without making some kind of impact.

And we have a choice. Certainly everybody in this room has a choice. Some people don’t have that much choice in their lives but we do. And if we start thinking about the consequences of the choices we make each day, the little things: what we buy, what we eat, what we wear, where did they come from, how was it made, did it result, the making of it, in cruelty to animals, was it child slave labour in a faraway place, did it harm the environment, that kind of thing, then we start making wiser choices. We can also ask ourselves do we really need it, is it necessary, do we have to buy this thing? And so, I feel that the biggest problem that people face today, is yes, we are getting wiser and wiser about what’s happening to the planet but it’s daunting.

If you think about everything, it’s daunting. And I’m one person, what can I do? There’s no point in doing anything because I’m helpless and hopeless. And so, people do nothing and they shut it all away, and they don’t even think about it. They don’t want to think about it because that would be depressing. So, it’s this apathy that has to be overcome and I found particularly with young people that when they start realising that yes, me alone, I can’t do anything but when there’s hundreds or thousands or millions or maybe eventually billions of people all making the right choices, all trying to leave a slightly lighter ecological footprint, then we begin moving to the kind of world that we can be happier to leave to our descendants.

So, that’s how Roots and Shoots was born. That was its main message that every individual matters and has a role to play, and makes a difference. And why is it called Roots and Shoots?

Well, you have beautiful trees in this country. I was just in a little park outside somewhere near here, and there were these strangling figs. They are such gorgeous things, we took photographs. And this strangling fig, when it starts, it’s from a very tiny little seed, and from that tiny little seed, little roots appear and little tiny shoots. And you can pick it up, and how teeny and weak and fragile it seems but it’s, you know what I call it, it’s a magic. It’s a life force in that seed so powerful that those little roots to reach the water can work though rocks and eventually push them aside. And that little shoot, to reach the sun, can work its way through cracks in a brick wall or a pavement, and eventually, break it down.

So, Roots and Shoots is hope that hundreds and thousands of young people around the world can break through and make a difference. And we are now in almost 100 countries. We started in Malaysia last year but there’s already over 50 groups in 50 different schools, thanks to the volunteers in Roots and Shoots, and TP Lim who is the chairman. I wouldn’t be here but for him. Stand up, TP, and where are the Roots and Shoots volunteers? You stand up too, I don’t know where you are, I can’t see but they’re there. (Claps)

So, to give you a tiny taste of what Roots and Shoots is doing around the world. Every group chooses three kinds of projects to make the world better. One to help people, one to help animals, one to help the environment. And the kind that they choose will depend on how old they are because we now have members from kindergarten all the way to university. It will depend if they are rich or poor, it’ll depend on the country that they are in or the part of the country that they are in because the problems will be different and the solutions will be different. But basically, it’s about talking about the problems, deciding what you can do and rolling up your sleeves and getting out. It’s about taking action.

And this little tiny four minutes of a film will give you just a little idea of what’s going on around the world.

(Video clip plays)

Well, maybe you can understand why my greatest reason for hope is the young people, and as I’m travelling around the world, everywhere I’m greeted with these shining eyes and young people of all ages wanting to tell Dr Jane what they have been doing, what they plan to do to make world a better place. And it’s growing so fast, this programme, and I think it’s because young people feel so empowered when they see the difference they make. When they see a place that was bare, and a forest beginning to grow back, when they remove invasive species, when they plant mangroves, when they raise money to help the victims of tsunamis or earthquakes. There are so many, many projects that these young people think of and take action and make change. It isn’t that young people can change the world, they are changing the world and that’s my greatest reason for hope.

But I have four other reasons for hope, and we wanted to talk about hope this evening.

My next reason is this human brain.

And yes, we have done some pretty bad things with our brain, we still are doing some pretty bad things with this amazing intellect of ours, but think of all the good things that are being done. Think of all the technology that’s been created that will enable us to live in greater harmony with this planet, the clean green energy. And if governments would just subsidise that, instead of always subsidising fossil fuel, then it would start to really bloom and we’d move much faster towards the kind of world we all want.

And the human brain is working in individuals too. We are learning that we can make a difference, we are learning to make different life choices which makes us feel better. Luckily when we do something, especially if it’s a bit hard, it makes you feel better and that’s really lucky. So, the human brain is my next reason for hope.

The resilience of nature.

Around Gombe, there were these bare hills. If you fly over it today, there are no more bare hills. The trees are growing back, that magic in the seeds in the soil is working, we haven’t even had to plant the trees there. And in Malaysia, there were two animal species that were on the brink of extinction and that’s the leatherback turtle and the green turtle, and they are now making a comeback.

And your forests in Sabah are being protected, I was hearing about that this morning, large areas of forests being protected, plans made to protect it even more and people determined to fight, to go on, so that the orang utans will have a home. And all the other extraordinary creatures in those forests will survive for your great-great grandchildren. And this is happening all over the world, and so the resilience of nature is one of my great reasons for hope. And I’ve seen it happening, I’ve seen it happening in so many countries.

And then, social media.

That is fairly new, I hadn’t thought about it before but I was in New York two years ago, and there was a climate march. And it was arranged by, I don’t know who arranged it but Al Gore was there and Ban Ki-moon. And the organisers hoped for about 80,000 people, in fact 400,000 people, the police had to stop more coming. So, what was happening? Everybody was on their little gadgets, you know facebooking and tweeting and twittering, and all the different things that get done these days. And there were also people on cell phones, I could hear them, I could hear what they were saying. And they were saying come and join us, it’s great weather, there’s all these famous people here. One of them said, I just saw Leonardo DiCaprio, one of them said I saw Angelina Jolie and one of them truly said I saw Jane Goodall. Yes!

That was happening in major cities around the world. It was said to be the biggest gathering of human beings around a single issue in the history of the Earth. So where in the old days, we would write letters and drop them through letter boxes, or we would make long telephone calls and gather as many people as we could for a demonstration or something, now, we can just spread it out around the world and get all these different people coming together. It’s very powerful.

And finally, my last reason for hope is the indomitable human spirit.

And this is something very special. There are people who, you know they suffered the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune as Shakespeare said, they have been knocked down, they have perhaps lost all their savings, people have fled the country where they grew up because of war and violence, and arrive as refugees with nothing and yet, because of this indomitable spirit, somehow they find a way forward and make a living for themselves.

And there are icons like Nelson Mandela, like Martin Luther King, I’m sure you have your own in this part of the world. And then, there are those people who overcome tremendous physical disabilities and lead lives that are shining inspiration to everybody around them. And that’s why I carry Mr H, you probably saw him in the piece of film. And Mr H is now 24 years old. He was given to me for my birthday 24 years ago by a man called Gary Horn which is why he is Mr H, who thought he was giving me a stuffed chimpanzee. Well, Gary Horn was blind, I made him hold the tail. And Gary Horn, having been blinded at 21 in the US Marines, for some odd reason, decided that he wanted to become a magician.

So everybody said, ‘But Gary, you can’t be a good magician if you can’t see.’ He said, ‘well, I can try.’ And he’s such a good magician that the children don’t realise he’s blind. And at the end, he’ll tell them and say ‘things may go wrong in your life because we never know. But if they do, don’t give up, there’s always some way forward.’ And he does sky diving. I mean I think it’s crackers to jump out of a plane anyway but to jump out into a pitch black world is the height of insanity. But anyway, he does it. And he has just produced a book called the Blind Artist. He paints, he’s learnt to paint, he has done an amazing portrait of Mr H just by holding him and feeling him, and putting it on paper. And in the book, he explains how he does it, how he does all these extraordinary pictures that he has produced. So I’m sure every single of you has had experience of this indomitable human spirt.

There are hundreds of stories, and so, those are my reasons for hope.

The young people all around the world, not just Roots and Shoots, so many other youth organisations. There is a new sense of urgency in young people. They seem to be growing up faster, they seem to have more sense of responsibility. And once they are educated and empowered to take action, there’s no limit to the effort that they put in to making this a better world. And then, this amazing human brain that can enable us to live in a very different way, if we will only push that side of it. And then, the resilience of nature, the power of social media, and that, of course, is due to the amazing brain. And then, the indomitable human spirit.

So, I want to thank all of you for coming tonight. And it is wonderful to look around and see so many faces in this lovely setting. So, I hope that this message of hope will inspire you to just think a little bit more about the way you live because that’s what’s going to make the difference. And that’s what’s going to enable you to go to sleep with a happier mind every night. And that’s my greatest hope for the future. Thank You.